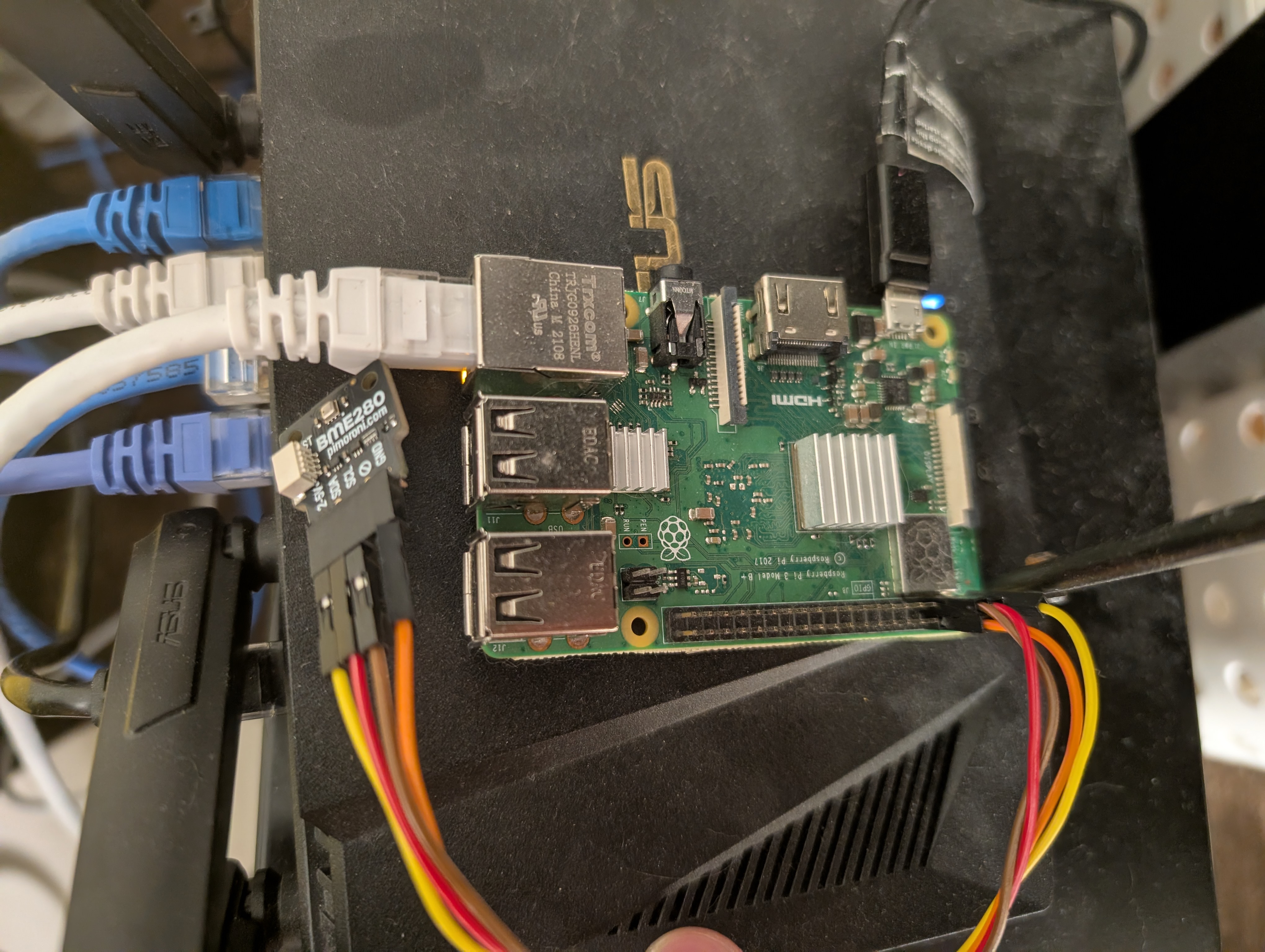

With the growing pile of unused SBCs and various sensors on my workbench, I pondered about how I could put some of these to good use. And then it hit me:"Aha! I will make a Raspberry Pi based weather station! Surely no one has done that before!"

This idea has been quite literally beaten to death.

Anyways, the main idea here is that I wanted my weather station to first take a temperature, pressure and humidity reading, using a BME280 sensor and then send that off to a webserver. This weather data would then be accessible to anyone who wishes to view it! Pretty neato if I do say so ( ▀ ͜͞ʖ▀).

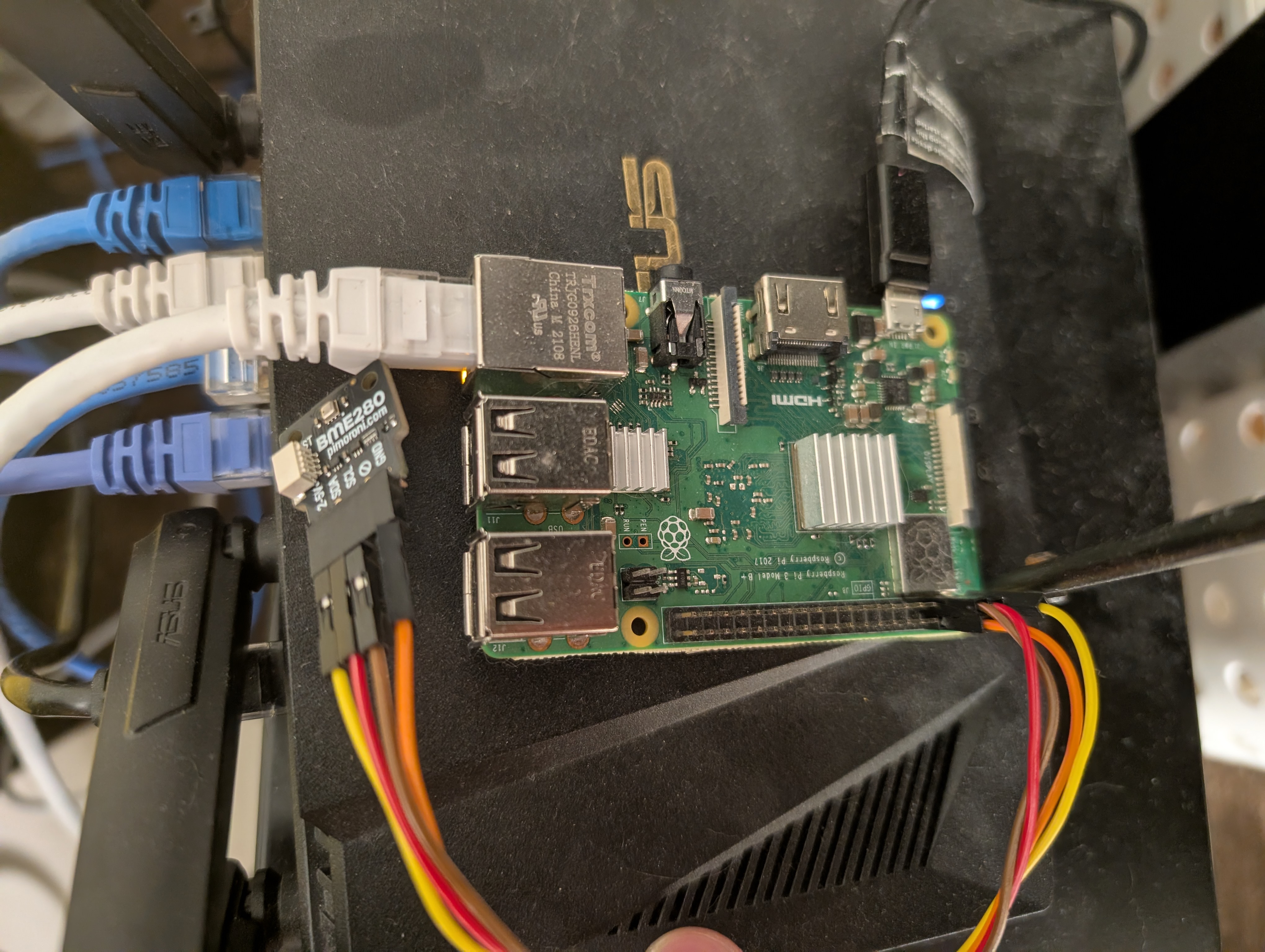

Thankfully (or unfortunately, depends what kind of person you are), most of the work in this project relies on code to make it work. Therefore, the wiring is extremely straight forward. Please see below for a very simple wiring diagram.

First and foremost, we need to install some boilerplate code and libraries so that our Raspberry Pi can properly talk to the

BME280. Instead of simply regurgitating the very clear instructions that have already been created, you can head over to this Github page to find the installation instructions. Do not forget to enable I2C on your Pi

or you will not be able to use the BME280 at all!. Once the library is installed, you should be able to locate some example code for the BME280 at

[wherever_you_installed_your_library]/bme280-python/examples/, specifically, the all-values.py file. In order to get up and

running with

the sensor as fast as possible, I found that it was very convienient to simply modify this file instead of starting from scratch (A.K.A I'm lazy

¯\_(ツ)_/¯). To give you a quick look at what the all-values.py file looks like, here it is below.

1. #!/usr/bin/env python

2.

3. import time

4.

5. from smbus2 import SMBus

6.

7. from bme280 import BME280

8.

9. print(

10. """all-values.py - Read temperature, pressure, and humidity

11.

12. Press Ctrl+C to exit!

13.

14. """

15. )

16.

17. # Initialise the BME280

18. bus = SMBus(1)

19. bme280 = BME280(i2c_dev=bus)

20.

21. while True:

22. temperature = bme280.get_temperature()

23. pressure = bme280.get_pressure()

24. humidity = bme280.get_humidity()

25. print(f"{temperature:05.2f}°C {pressure:05.2f}hPa {humidity:05.2f}%")

26. time.sleep(1)

This is now an excellent time to run this example code and see if you are able to get any values! If everything works, you should see a temperature, pressure and humidity reading once every second. If Murphy's Law has a firm grasp on you, there was most likely an issue with the Python virtual environment somewhere or I2C was not enabled on the Pi.

Assuming everything is working now, we can start adding our own code to this example code to make it a little more interesting. Let's first take a look at the changes that I made an I will explain them as we move through them.

1. #!/usr/bin/env python

2.

3. import time

4.

5. import requests

6.

7. import json

8.

9. from smbus2 import SMBus

10.

11. from bme280 import BME280

12.

13. print(

14. """all-values.py - Read temperature, pressure, and humidity

15.

16. Press Ctrl+C to exit!

17.

18. """

19. )

20.

21. # Initialise the BME280

22. bus = SMBus(1)

23. bme280 = BME280(i2c_dev=bus)

24.

25. # initialize weather data dict and weather data averages

26. data = {"temperature": 0.0, "pressure": 0.0, "humidity": 0.0, "time": 0}

27. temperature_avg = 0.0

28. pressure_avg = 0.0

29. humidity_avg = 0.0

30.

31. # get 20 readings for each parameter then calculate their average

32. # save average to data dict

33. for i in range(1, 21):

34. temperature = bme280.get_temperature()

35. pressure = bme280.get_pressure()

36. humidity = bme280.get_humidity()

37.

38. temperature_avg += temperature

39. pressure_avg += pressure

40. humidity_avg += humidity

41.

42. time.sleep(1)

43.

44. temperature_final = temperature_avg / 20.0

45. pressure_final = pressure_avg / 20.0

46. humidity_final = humidity_avg / 20.0

47. unix_time = time.time()

48.

49. data["temperature"] = temperature_final

50. data["pressure"] = pressure_final

51. data["humidity"] = humidity_final

52. data["time"] = unix_time

53.

54. print(f"{temperature_final:05.2f}C, {pressure_final:05.2f}hPa, {humidity_final:05.2f}%, {unix_time:05.2f}s")

55.

56. # POST JSON data dict to windsorweather.xyz

57. response = requests.post(url="https://windsorweather.xyz/receiveData.php", json=data)

58. print(f"Status code for POST request: {response.status_code}")

Starting on lines 25-29, we initialize a new array which will contain our BME280 sensor readings as well as our averages for temperature, pressure and humidity which we will calculate later. On lines

31-46, we take 20 readings from the BME280 for all three metrics (temperature, pressure and humidity), then calculate their averages. The reason for this averaging is that the BME280 may not always give

us an accurate reading, so by averaging 20 readings, we have a sort of buffer that can be used to avoid these errors (that's the idea anyways). From lines 47-58, we simply store all of our readings

(including a unix time value) into our data dictionary and use the Python Request library (super cool library with crystal clear documentation,

definitely check it out) to create a POST request to our weather data server, speicifically the receiveData.php page (more on this later).

Now that's a wrap for the client-side code! All that is left to do now is work out the server-side code to receive the data from the Pi, parse it and then display it on a webpage. For the sake of this demo (and because I am lazy ( ゚ヮ゚)), I am demonstrating code that is slightly above the bare minimum to give you an idea of what this would look like.

Moving onto the server side of things, this code can essentially be broken down into 3 distinct blocks:

In theory (and in practice, honestly), these are some pretty simple tasks to accomplish but since this is only my second PHP project, I

must say that I am quite proud of it (▀̿Ĺ̯▀̿ ̿). Enough with the yapping though, let's take a look at the code and I'll try to break it down as

best as I can, starting with the receive.php file.

1. <?php

2. $path = "/var/www/windsorweather/dataFiles/weatherdata.json"; // file path to store weather data

3. $raw_string = file_get_contents("php://input"); // get contents of input file stream

4.

5. // first need to check if $raw_string contains any json data,

6. // then we check if it has numerical data

7. // if data good, write data to file

8. // if data not good, do not write to file and keep last good data

9. $data_array = json_decode($raw_string, true);

10.

11. if($data_array) {

12. echo "decode successful<br>";

13. foreach($data_array as $value) {

14. if(!is_numeric($value)) {

15. echo "Error parsing weather data";

16. exit(1); // exit script with error code

17. }

18. }

19.

20. echo "values are numbers<br>";

21.

22. echo $data_array["temperature"];

23. echo $data_array["pressure"];

24. echo $data_array["humidity"];

25. echo $data_array["time"];

26.

27. $fp = fopen($path, "w"); // open file to write data to (will erase current contents of file)

28. fwrite($fp, $raw_string); // write weather data to file

29. fclose($fp); // close file pointer

30.

31. echo "wrote to file<br>";

32. }

33. else {

34. echo "Error receving weather data, could not decode<br>";

35. exit(2);

36. }

37.

38. exit(0)

39. ?>

Starting with lines 2-9, we first define the path for where our weather data will reside on the webserver. This path will be important later for when we need to save the new data we receive.

Next on line 3, we use the file_get_contents() funciton with the php://input input stream to read the raw data from the HTTP request that this web page receives. In our

case, we are storing this raw data into a string variable called raw_string. Line 9 is where our first validation check comes in: by using the json_decode() function

with our raw_string as an argument, we can quickly determine if this request contains any json data in it. If it does, we continue with the rest of the script. If not, we simply

exit with a status code of 2 (anything other than 0 would technically work here). Continuing through lines 11-25, we are simply using a foreach loop to confirm that every element of

our associative array is numerical. If it is not, we exit the script with a differnt status code. Otherwise, we continue and display these values for debugging purposes.

Lastly on lines 27-31, we are now fairly confident that what he have is in fact weather data and so we can begin writting it to a file on the web server to save it. Similarly to almost any other language that allows

reading and writting to files, we first create a file pointer pointing to the file that we wish to access, then, in our case, we call the fwrite() to actually write the weather to

the file at the location that was specified all the way at the begining of the code. And just like any responsible programmer we clean up after ourselves by closing our file pointer once we are

done with it.

With all of that mentioned, we have completed 2 of our 3 objectives: we have received the data and parsed it. The only thing left to do now is to actually display it on a web page that the user can actually visit, and below is the code that does exactly that!